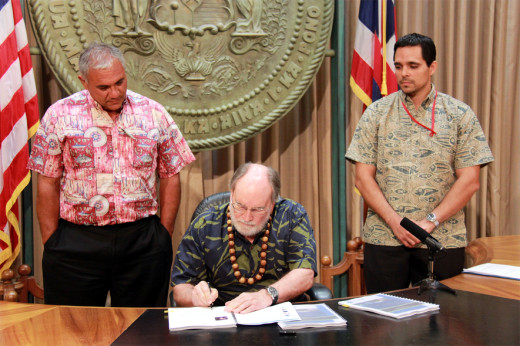

DLNR chair William Aila (left) and Office of Planning Director Jesse K. Souki (right) watch as Governor Neil Abercrombie signs the Hawaii Ocean Resources Management Plan

HONOLULU, Hawaii – A plan to ensure the sustainable use of Hawaii’s ocean and coastal resources was signed by the governor today on Oahu.

The Ocean Resources Management Plan identifies 11 management priorities for the next five years with the goal of conservation for current and future generations. The state says the effort fostered collaboration across government agencies, and was developed with the participation of county, state and federal agencies responsible for ocean and coastal resources.

“It is essential that government agencies at all levels work together to address Hawaii’s resource challenges,” Gov. Abercrombie said in a media release. “Our lives are intertwined with the natural resources of these islands, from the local economy to our island way of life. This plan provides a clear roadmap for achieving a necessary balance between use and preservation.”

ARCHIVED LIVE STREAM – Hawaii Ocean Resources Management Plan signed

The state says this 2013 Ocean Resources Management Plan is considered an update of the 2006 ORMP. It continues the new direction and course of action. It is the fourth ORMP for Hawai‘i. This time around the plan makes use of new terms – the buzzwords the current administration and the state’s other latest policies – such as the Hawai‘i 2050 Sustainability Plan and the New Day Plan. The state also tried to produce a more reader- and user-friendly document with new graphics and editing.

The plan acknowledges pressures on the ocean and critical issues that need to be addressed, like urbanization, tourism impacts, military use, shoreline access, coastal hazards and sea level rise, marine debris, damage to coral reefs, and watershed management, among other things.

To properly address these concerns, the plan lays out “Three Perspectives” that were incorporated in the 2006 document:

Perspective 1: Connecting Land and Sea

Careful and appropriate use of the land is required to maintain the diverse array of ecological, social, cultural, and economic benefits we derive from the sea.

Perspective 2: Preserving our Ocean Heritage

A vibrant and healthy ocean environment is the foundation for the quality of life valued in Hawaii and the well-being of its people, now and for generations to come.

Perspective 3: Promoting Collaboration and Stewardship

Working together and sharing knowledge, experience, and resources will improve and sustain our efforts to care for the land and the sea.

The plan also introduced 11 priorities that fit into the three perspectives. In the document, the state lays out the goals it hopes to accomplish following these priorities. For the priority list presented below, we have published the “background” and “Target – Where we want to be” for each item. It should be noted there is much more written about each priority in the full 2013 Ocean Resources Management Plan document.

| 1. Appropriate Coastal Development

One of the goals of the CZM Program is to ensure that appropriate setbacks and protections are put into place to ensure appropriate development and structures along the coastal areas. Appropriate coastal development addresses the issues identified under the CZM Act, including coastal hazards (including sealevel rise), historic resources, coastal ecosystems, and Hawaii’s economy for current and future generations. The most difficult issues to address are coastal development issues that stem from development that already exists. While great strides have been made, there are many structures “grandfathered” under old codes, and continued pressure from landowners for legislative exemptions from regulatory review. This pressure can be very contentious and stressful for county and state permitting agencies. Target – Where we would like to be

2. Management of Coastal Hazards One of the key objectives of The National Ocean Policy is to “strengthen resiliency of ocean communities and marine environments…and their abilities to adapt to climate change impacts and ocean acidification.” Disaster avoidance measures would include institutional and governmental measures to reduce risks from coastal hazards. Target – Where we would like to be

3. Watershed Management The State of Hawai‘i has approximately 580 watersheds in the state of Hawai‘i as listed in the Hawai‘i Watershed Guidance (2010). The DLNR Division of Forestry and Wildlife (DLNR-DOFAW) defines Watershed Partnerships statewide, which include both public and private land. There are currently eleven Watershed Partnerships as shown in the figure at right. The ORMP addresses watersheds from two different viewpoints, the mauka watersheds that provide the water quantity and the watersheds moving makai that affect the ocean water quality. Ensuring the health of the water supply, allowing for water recharge, and preserving good water quantity entails taking care of the watersheds. Water flows from mauka to makai and ends in the ocean, filling the streams, providing species habitat, and improving the coastal and nearshore water quality. Good quality and sufficient quantity of water is needed feed the island’s reef systems. Target – Where we would like to be

4. Marine Resources Marine debris is defined as any solid material disposed of or abandoned in the marine environment. It is a chronic problem for Hawaiʻi that can be introduced by ships, arrive as wash from rivers, streams, and storm drains, or reach Hawaii’s shores from ocean currents. Depending on its origin, marine debris also has the potential to introduce invasive species. Examples vary greatly, but include plastic bags, bottles, rubber slippers, derelict fishing gear, equipment, and nets, and abandoned or derelict vessels. Causes may be accidental, natural disaster, illegal dumping, or abandonment of vessels. Land activities that can end up in the ocean include littering, dumping, improper waste management, and industrial losses. Also included are stormwater runoff, materials washed down storm drains, or trash deposited during storms, high winds, or waves. A special case of marine debris is the materials adrift in the ocean or washing ashore that originated in the Japanese earthquake and tsunami of March 2011. These are referred to as Japan Tsunami Marine Debris (JTMD). Aquatic invasive species (AIS) may be introduced in other ways through shipping activity, typically arriving through biofouling (previously referred to as hull fouling) or ballast water, or through purposeful introduction such as dumping. The majority of non-indigenous aquatic species seen in Hawai‘i today arrived on vessels as biofouling or in their ballasts. Many of these species cause negative impacts to important ecosystems. Aquatic invasive species pose significant threat to Hawaii’s native plants, animals, ecosystems, economy as well as the human population. While most island ecosystems in the world are highly vulnerable, Hawaii’s isolation makes its ecosystems even more vulnerable than others. Hawaiʻi contains 40% of the threatened and endangered species in the U.S. But as a major transportation hub and tourist destination, the threat of invasion can never be completely eradicated and requires constant vigilance. According to the National Marine Fisheries Service, Hawai‘i has the highest per capita non-commercial fisheries catch in the nation at 1.4 million fishing trips for a total near 2.7 million fish in 2011. For commercial fishing, the port of Honolulu ranks among the top ten fishing ports in the nations with $83 million dollars of fish landed in Honolulu Harbor in 2011. Target – Where we would like to be

5. Coral Reef Many of the greatest threats to the reefs come from land-based sources of pollution, including sediment, nutrients, cesspools, sewer treatment plant overflow, and road run-off. Excess nutrients promote the growth of algae that compete for space on the benthic reef surfaces and affect the ability of coral to establish and grow. Another threat to the health of reefs is grounded vessels. Climate change impacts on coral include effects from ocean warming, coral bleaching, and ocean acidification. Coral bleaching is becoming more frequent as the oceans warm, with predictions that by 2050 many of the reefs of the Pacific will bleach annually. Increased acidification of the ocean is caused by rising levels of carbon dioxide absorbed by sea water. With ocean acidification, less carbonate is available for coral reefs to build their calcium carbonate skeletons, causing coral loss. Coral cover throughout the Pacific is expected to decline 15% to 35% by 2035. Target – Where we would like to be

6. Ocean Economy Hawaii’s economy is dependent on the health of the ocean. The marine-related industries of fishing, aquaculture, tourism, recreation, and shipping provide approximately 15% of Hawaii’s civilian jobs. According to the National Ocean Economics Program (NOEP), in 2010 Hawaii’s ocean economy accounted for 100,215 jobs and over $3.1 billion in wages. According to UH College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources, Hawai‘i residents eat more seafood per capita than the rest of the United States. In 2010, Hawai‘i residents spent $330.68 per capita or 11.4% of their total food consumption at home and in restaurants. This is over twice as much as the U.S. per capita of $143.68. Hawaii’s aquaculture value of shellfish and finfish is $2,000,000 annually, and expected to increase. Shellfish rules were created in the early 1980s to accommodate a fledgling shellfish industry, and because the industry did not survive, the DOH lab lost its Food and Drug Administration (FDA) certification to analyze shellfish growing waters and shellfish meat samples. In recent years, there has been a concerted effort to create a viable shellfish industry, and the DOH Food Safety Program and DOH lab have revived the shellfish sanitation program. Target – Where we would like to be

7. Cultural Heritage of the Ocean Native Hawaiian access and gathering rights are protected by state laws and Hawaiians built rock-walled enclosures in near shore waters to raise fish, an integral part of the ahupuaʻa. Fish entered through a wooden gate or sluice in the stone wall on the seaward side and as they grew, they became too large to return to the open ocean. In ancient Hawai‘i, it was estimated that there were 488 fishponds statewide, and more than 75 fishponds were in production on Molokaʻi alone. Yet the fishponds went out of use, became contaminated, and most disappeared. Target – Where we would like to be

8. Training, Education, and Awareness The science and information on the ocean ecosystems and climate change are rapidly changing. Data collection and monitoring both yield new information. Institutional responsibilities, rules, and regulations need to be understood by State and County agency staff so that they can make informed decisions. While networking such as in the ORMP Working Group provides a valuable exchange of knowledge, there is a need for a more systematic way for staff to receive basic and advanced training. Target – Where we would like to be

9. Collaboration and Conflict Resolution The ORMP Policy and Working Groups were established in 2007 and have been meeting regularly since then. Both groups work on implementation of the ORMP. They provide a forum for state agencies and county and federal partners to share information, improve coordination, and prevent duplication. They offer an opportunity to increase partnerships and collaborations for effective and efficient conservation efforts in the Hawaiian Islands Target – Where we would like to be

10. Community and Place-Based Ocean Management Projects During the Demonstration Phase a variety of place-based initiatives and models for integrated government and community emerged. Many projects involve active involvement of community members who worked to restore part of an ecosystem and began to monitor and watch that ecosystem. As projects continue forward and results are seen, they attract additional interest and resources. (NOTE: The document mentions Honuʻapo Estuary, Hilo Bay, Puʻu O Umi Natural Reserve and Kohala Natural Reserve as Demonstration Phase examples of place-based community projects and stewardship) Target – Where we would like to be

11. National Ocean Policy and Pacific Regional Ocean Initiatives The National Ocean Policy (NOP) was created in 2010 by President’s Executive Order 13547, which was based on the Final Recommendations of the Interagency Ocean Policy Task Force. The NOP creates a framework for collaboration to enhance the country’s ability to maintain healthy, resilient, and sustainable oceans, coast and Great Lakes resources. The framework developed calls for nine regional planning bodies (RPB). Hawai‘i is a member of the Pacific Island Regional Planning Body (PIRPB). The One objective of the NOP is to improve spatial information on the condition of the oceans. This information is meant to aid the development of public policy and decision making. The goal of the PIRPB is to complete a coastal and marine spatial plan for the Pacific Islands Region. The state also desires to develop a coastal and marine spatial tool, a mapping tool that is GIS based and tied to the state’s GIS system. In the long term, the state will develop a coastal and marine plan for Hawai‘i. Target – Where we would like to be

|

The state says the 11 priorities articulated in the plan are based on community outreach conducted in all four counties through public meetings, oral and written submissions, and social media.

“The 11 management priorities address resource management challenges that can only be achieved through a statewide, coordinated effort among various government and community partners,” said Jesse Souki, director of the state Office of Planning. “It addresses some of the greatest challenges of our time, including the impacts of climate change and balancing economic, cultural and environmental considerations to ensure sustainable stewardship of our resources.”

For all the details, you can download the 2013 Ocean Resources Management Plan from the State of Hawaii website.

by Big Island Video News3:41 pm

on at

STORY SUMMARY

HONOLULU, Hawaii – A plan to ensure the sustainable use of Hawaii’s ocean and coastal resources was signed by the governor today on Oahu. The Ocean Resources Management Plan identifies 11 management priorities for the next five years with the goal of conservation for current and future generations. The state says the effort fostered collaboration […]