(BIVN) – From this week’s Volcano Watch article, written by U.S. Geological Survey Hawaiian Volcano Observatory scientists and affiliates:

As people from around the world are captivated by episodic lava fountaining during the ongoing Kīlauea eruption in Halemaʻumaʻu, let’s use the current pause and transition our attention back to the details of another recent eruption—Mauna Loa in 2022.

Many residents remember Mauna Loa—the largest active volcano on Earth—roaring awake after decades of slumber with a dynamic summit and Northeast Rift Zone (NERZ) eruption in late 2022. Geophysical instruments recorded many major, and even subtle, details the night of the 2022 Mauna Loa eruption onset. Here we’ll explore some of these monitoring data observations that give us clues as to what was happening beneath the surface.

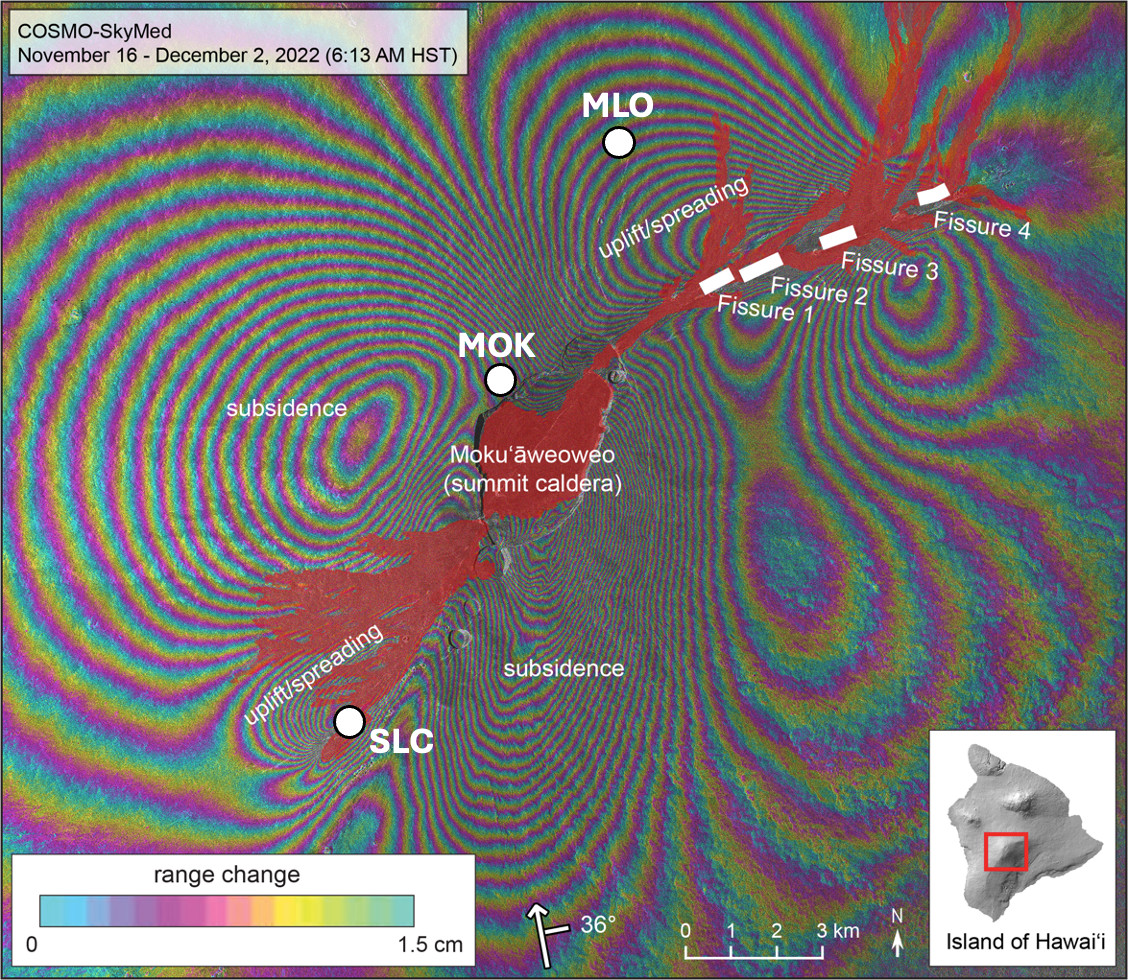

USGS: “Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR) image of Mauna Loa spanning November 16 to December 2, 2022. Concentric patterns of colored fringes indicate the complex pattern of deformation during the 2022 Mauna Loa eruption. Lava flows are shown by light red areas and summit tiltmeter site locations are shown with white circles.”

Around 10:20 p.m. HST on November 27, 2022, the USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO) monitoring networks detected rapid changes in Mauna Loa’s summit area. A swarm of small, shallow earthquakes occurred beneath the caldera and just south of the summit, lasting about an hour. At the same time, tiltmeters at Mauna Loa’s summit began to record significant ground deformation—a sign that magma was moving rapidly toward the surface.

By 10:50 p.m., a tiltmeter designated MOK and located on the northeast rim of Mokuʻāweoweo (Mauna Loa’s summit caldera), measured inflationary tilt of over 100 microradians—pointing downwards to the northwest and away from the summit, which indicated that magma was continuing to rise upward from below. Tremor, a seismic signal often associated with magma movement, was also detected just minutes later.

At 11:21 p.m. HST, the eruption began. Webcam imagery confirmed fissures had opened within Mokuʻāweoweo, and that lava was flooding the caldera floor. Almost immediately, the MOK tiltmeter showed rapid deflation, reflecting that magma from the summit reservoir was spilling out onto the surface.

Image from a temporary USGS research camera positioned on the north rim of Mokuʻāweoweo, showing the eruption in the summit caldera of Mauna Loa volcano on Nov. 27, 2022.

Meanwhile another tiltmeter designated SLC and located southwest of the summit—just above Mauna Loa’s Southwest Rift Zone (SWRZ)—began to show dramatic changes as well. By the early morning of November 28, the instrument had recorded over 500 microradians of tilt towards the north and northwest, and, soon after, it went off-scale because the amount of tilting was higher that it was designed to measure. The magnitude and direction of these readings were puzzling, as they weren’t exactly what would be expected if magma migrated toward the SWRZ, but any movement on this tiltmeter was concerning. Such a scenario could result in lava flows threatening communities downslope, such as Hawaiian Ocean View Estates or others on the south Kona coast.

However, no deformation was seen at a tiltmeter farther down the SWRZ (designated BLB), which suggested that the magma had not continued in that direction. Instead, the eruptive activity shifted northeast, and vents opened along Mauna Loa’s NERZ, feeding lava flows that mostly traveled north-northeast towards the Humuʻula Saddle. The eruption remained there until its end in mid-December. The large tilt magnitude measured at SLC was instead interpreted as a response to the summit reservoir’s extent and draining, not a sign of rift zone intrusion.

As the eruption continued, significant deflation was recorded at summit GPS stations. Between November 27 and December 10, 2022, the summit caldera subsided nearly 40 centimeters (16 inches). This signal decreased with distance away from the summit, but even sites on Mauna Loa’s flanks measured several centimeters of subsidence. Satellite radar imagery from Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR) showed additional complex patterns of ground movement, which indicate where magma either reached the surface or was very close to the surface.

The effects of the eruption were not limited to just Mauna Loa. GPS stations on neighboring volcanoes on the Island of Hawai’i, including Kīlauea and Hualālai, recorded small but measurable motion in response to deflation of Mauna Loa during the active 2022 eruption. Some stations at Kīlauea began migrating northwest—toward Mauna Loa—within a single day of the eruption starting. This inter-volcano response illustrates how Mauna Loa’s activity can affect stress fields across the island and potentially influence other volcanic systems.

Currently, instruments on Mauna Loa show low levels of seismicity and only minor inflation near the summit as the volcano recovers from the 2022 eruption and magma replenishes the reservoir system. Still, we know Mauna Loa will only slumber for so long, and another eruption will occur years or decades into the future. But the public can rest assured, while Kīlauea continues to erupt with its impressive lava fountains, HVO scientists are also continuing to closely monitor and study the now-quiet Mauna Loa behind the scenes as well as other volcanoes in Hawaii and American Samoa.

by Big Island Video News7:25 am

on at

STORY SUMMARY

ISLAND OF HAWAIʻI - Scientists look back on the most recent eruption of Mauna Loa, which started late on November 27, 2022, after months of heightened unrest.